This term has other meanings, see Karasuk.

| City Karasuk Flag | Coat of arms |

| A country | Russia, Russia |

| Subject of the federation | Novosibirsk regionNovosibirsk region |

| Municipal district | Karasuksky |

| urban settlement | Karasuk city |

| Coordinates | 53°44′00″ n. w. 78°02′00″ E. long / 53.73333° north w. 78.03333° E. d./53.73333; 78.03333 (G) [www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=53.73333&mlon=78.03333&zoom=12 (O)] (Z)Coordinates: 53°44′00″ N. w. 78°02′00″ E. long / 53.73333° north w. 78.03333° E. d./53.73333; 78.03333 (G) [www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=53.73333&mlon=78.03333&zoom=12 (O)] (I) |

| Chapter | Gofman Alexander Pavlovich |

| Based | in 1915 |

| First mention | XVIII century |

| City with | 1954 |

| Square | 35.76 km² |

| Center height | 110 |

| Population | ↘27,332[1] people (2016) |

| Density | 764.32 people/km² |

| National composition | Russians, Ukrainians, Germans, Kazakhs, Armenians |

| Names of residents | Karasuchan, Karasuchan, Karasuchan |

| Timezone | UTC+7 |

| Telephone code | +7 38355 |

| Postcode | 6328XX(60-68) |

| Vehicle code | 54, 154 |

| OKATO code | [classif.spb.ru/classificators/view/okt.php?st=A&kr=1&kod=50217501 50 217 501] |

| Day of the city | first Saturday in July |

| Karasuk Moscow |

| Novosibirsk Karasuk |

Audio, photo and video

on Wikimedia Commons

K: Settlements founded in 1915

Karasuk

(from Turkic, cf. Chulym. Karasuk, Sibtat. Karasu, South Alt. Karasuu, Khak. Karasug, “black water”) is a city (since 1954) in Russia, the administrative center of the Karasuksky district of the Novosibirsk region.

Geography

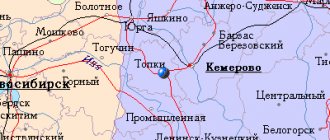

Karasuk is the administrative center of the district, located in the north of the Kulunda steppe in the southwestern part of the Novosibirsk region. The distance to Novosibirsk is 384 km. In accordance with the decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR dated June 3, 1954, the workers' village of Karasuk received the status of a city of district subordination. Karasuk appeared at the beginning of the twentieth century during the construction of a branch from the Trans-Siberian Railway, the Tatarskaya - Slavgorod railway line. The railway is still a city-forming factor in the city, connecting it with Novosibirsk, Barnaul, Omsk, and Kulunda. After the collapse of the USSR, Karasuk found itself on the border with sovereign Kazakhstan and acquired the status of a border city.

Story

The founding date of Karasuk is considered to be the emergence of the village during the construction of the Altai Railway in 1912.

The first peg for construction was driven in in May 1912, not far from the place where the Karasuk-1 station is located. Construction of the railway on the Tatarskaya - Slavgorod section began in 1913. By the summer of 1916, the roadbed was brought to Karasuk, and already in January 1917, the regular movement of a goods and passenger train was announced, which arrived in Karasuk once a week. The station got its name from the Karasuk River, near which it was located.

The station developed quite quickly. Initially as part of the Chernokuryinskaya volost, then the village council. Until 1933, on the territory of the Novosibirsk region there were three settlements called Karasuk. Since 1929, the village of Cherno-Kurya has been renamed Karasuk. Accordingly, the area called Chernokuryinsky became Karasuksky. Until 1933, another regional center, the village of Krasnozersky, was also called Karasuk. After being renamed Karasuk, Black Kurya remained the center of the district for several years, and then it moved closer to the railway station.

In 1943, a single workers' settlement with a single name was formed. On June 3, 1954, in accordance with the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR, the workers' village of Karasuk was transformed into a city of regional subordination.

In 1960-1980, the city's infrastructure developed mainly due to the railway, which was and remains the city-forming center.

Education

There are six general educational institutions in the city: a gymnasium, a lyceum, three secondary schools and 1 basic school. There is a full-time and correspondence secondary school, a children's music school, a children's and youth center, an art school, a children's and youth sports school, Karasuk Polytechnic Lyceum (specialization: railway transport), PU No. 86 (specialization: agriculture) is currently closed, Karasuk Pedagogical College, also have representative offices of universities and colleges in Novosibirsk, Tomsk, Omsk and Berdsk on the basis of correspondence and distance learning for students. In the field of preschool education, there are 9 kindergartens in the city.

Sport

The main sports facilities of the city:

- Lokomotiv Stadium"

- Swimming pool "Sadko"

- SK "Molodost"

- SC "Dynamo"

- Youth and Youth Sports School

- Ski base

- Sports life of the city of Karasuk

- IV Interdistrict Spartakiad of Education Workers

- X Spartakiad “Health” March 28, 2011

- X Spartakiad “Health” March 12, 2011

- On February 12, in Novosibirsk, on the basis of the French gymnasium No. 16, volleyball competitions took place as part of the 1st regional sports day for education workers of the Novosibirsk region

Culture and art

Theater "On the Outskirts"

Founded by the Resolution of the session of the Council of Deputies of the city of Karasuk dated June 15, 2005. The founder was the administration of Karasuk. The only drama theater in the city. In 2009, it began its IV theater season. The theater's repertoire includes both adult and children's performances. In April 2009, “On the Outskirts” went on tour in the NSO. Artistic director of the theater “On the Outskirts” A.P. Kobets.

Cinemas

Currently there is a cinema "Cosmos" in the city.

Museum

Main excursions:

- “Through the hall of history of Karasuk and the region”

- "Hall of the Great Patriotic War"

- "Hall of Flora and Fauna"

- "Hall of Archeology and Paleontology"

- "Through the Art Gallery"

The museum also hosts major exhibition projects, visiting and exchange exhibitions. The Karasuk Local History Museum was one of the nine museum sites in the Novosibirsk region that were entrusted with holding exhibitions from leading Russian museums in 2014.

Population

As of January 1, 2022, in terms of population, the city was in 546th place out of 1,115 cities in the Russian Federation.

Gender composition

According to the 2010 All-Russian Population Census, the permanent population of the city was 28,586 people, of which 13,221 (46.2%) were men, and 15,365 (53.8%) were women.

National composition

According to the 1939 census: Russians - 55.8% or 4055 people, Ukrainians - 37.7% or 2735 people, Kazakhs - 3.1% or 226 people.

Famous people associated with Karasuk

- Yurchenko, Vasily Alekseevich - ex-governor of the Novosibirsk region[19]

- Russkikh, Leonid Valentinovich - Hero of the Russian Federation. Participant in the Ossetian-Ingush conflict, the First and Second Chechen wars,

- Timonov, Vasily Nikolaevich - Hero of the Soviet Union. Participant of the Great Patriotic War.

- Landik, Ivan Ivanovich - Hero of the Soviet Union.

- Karnaushchenko, Marina Nikolaevna - Russian track and field athlete, Master of Sports of Russia.

- Loginov, Evgeniy Yuryevich - deputy of the State Duma of the Russian Federation. Leader of the unregistered party "Russian Breakthrough".

- Sorokin, Zakhar Artemovich - Soviet pilot, hero of the Great Patriotic War, Hero of the Soviet Union.

- Smetanin, Grigory Andreevich - senior observer pilot of the 10th separate reconnaissance aviation regiment, captain. Hero of the Soviet Union.

- Orlov, Yakov Nikiforovich - major of the Soviet Army, participant in the Great Patriotic War, Hero of the Soviet Union.

- Molochkov, Grigory Aksentievich - lieutenant of the Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, participant in the Great Patriotic War, Hero of the Soviet Union.

- Klimovsky, Nikolai Afanasyevich - colonel of the Soviet Army, participant in the Great Patriotic War, Hero of the Soviet Union.

- Molozev, Viktor Fedorovich - colonel of the Soviet Army, participant in the Great Patriotic War, Hero of the Soviet Union.

- Nabatov, Vyacheslav Vasilievich - Russian Soviet painter, member of the St. Petersburg Union of Artists.

- Trakhimenok, Sergei Alexandrovich - writer, doctor of legal sciences, professor. Secretary of the Writers' Union of Belarus.

- Volkov, Andrey Alekseevich - lieutenant of the Soviet Army, participant in the Great Patriotic War, Hero of the Soviet Union.

- Rubezhansky, Pyotr Nikolaevich - Russian statesman and railway manager, advisor to the President of Russian Railways V. I. Yakunin.

Attractions

- Temple in the name of the Holy Apostle Andrew the First-Called.

- Monument to the heroes of the civil war.

- Locomotive-monument L-3609. Installed in 2005 in honor of the Hero of Socialist Labor Alexander Dorofeevich Parfenov and his assistant Valentina Burtenko.[20]

- Memorial of Military Glory. The names of more than 5,000 natives of the Karasuk region who died during the Great Patriotic War are immortalized on the pylons of the memorial, and 9 busts of fellow countrymen - Heroes of the Soviet Union are installed.[20]

- Memorial of Labor Glory. Opened in 2015. The first monument to home front workers in the Novosibirsk region.[20]

- Melkovsky mound (Lake Melkoe).

- Kurgan (village Blagodatnoe).

- Water tower built in 1915.[20]

- [archive.is/20130416151921/bolser.ru/photo/nature/karasuk_paysage/IMG_5140B.jpg Salt Lake] - healing mud and salt water that can keep a person afloat without moving (at the moment, it is adjacent to [archive.is/20130416181043 /bolser.ru/photo/nature/karasuk_paysage/IMG_5021A.jpg drainage canal] for draining swamp water from the city limits).

An excerpt characterizing Karasuk (city)

Rostov rode at a pace, not knowing why or to whom he would go now. The Emperor is wounded, the battle is lost. It was impossible not to believe it now. Rostov drove in the direction that was shown to him and in which a tower and a church could be seen in the distance. What was his hurry? What could he now say to the sovereign or Kutuzov, even if they were alive and not wounded? “Go this way, your honor, and here they will kill you,” the soldier shouted to him. - They'll kill you here! - ABOUT! what are you saying? said another. -Where will he go? It's closer here. Rostov thought about it and drove exactly in the direction where he was told that he would be killed. “Now it doesn’t matter: if the sovereign is wounded, should I really take care of myself?” he thought. He entered the area where most of the people fleeing from Pratsen died. The French had not yet occupied this place, and the Russians, those who were alive or wounded, had long abandoned it. On the field, like heaps of good arable land, lay ten people, fifteen killed and wounded on every tithe of space. The wounded crawled down in twos and threes together, and one could hear their unpleasant, sometimes feigned, as it seemed to Rostov, screams and moans. Rostov started to trot his horse so as not to see all these suffering people, and he became scared. He feared not for his life, but for the courage that he needed and which, he knew, would not withstand the sight of these unfortunates. The French, who stopped shooting at this field strewn with the dead and wounded, because there was no one alive on it, saw the adjutant riding along it, aimed a gun at him and threw several cannonballs. The feeling of these whistling, terrible sounds and the surrounding dead people merged for Rostov into one impression of horror and self-pity. He remembered his mother's last letter. “What would she feel,” he thought, “if she saw me now here, on this field and with guns pointed at me.” In the village of Gostieradeke there were, although confused, but in greater order, Russian troops marching away from the battlefield. The French cannonballs could no longer reach here, and the sounds of firing seemed distant. Here everyone already saw clearly and said that the battle was lost. Whoever Rostov turned to, no one could tell him where the sovereign was, or where Kutuzov was. Some said that the rumor about the sovereign’s wound was true, others said that it was not, and explained this false rumor that had spread by the fact that, indeed, the pale and frightened Chief Marshal Count Tolstoy galloped back from the battlefield in the sovereign’s carriage, who rode out with others in the emperor’s retinue on the battlefield. One officer told Rostov that beyond the village, to the left, he saw someone from the higher authorities, and Rostov went there, no longer hoping to find anyone, but only to clear his conscience before himself. Having traveled about three miles and having passed the last Russian troops, near a vegetable garden dug in by a ditch, Rostov saw two horsemen standing opposite the ditch. One, with a white plume on his hat, seemed familiar to Rostov for some reason; another, unfamiliar rider, on a beautiful red horse (this horse seemed familiar to Rostov) rode up to the ditch, pushed the horse with his spurs and, releasing the reins, easily jumped over the ditch in the garden. Only the earth crumbled from the embankment from the horse’s hind hooves. Turning his horse sharply, he again jumped back over the ditch and respectfully addressed the rider with the white plume, apparently inviting him to do the same. The horseman, whose figure seemed familiar to Rostov and for some reason involuntarily attracted his attention, made a negative gesture with his head and hand, and by this gesture Rostov instantly recognized his lamented, adored sovereign. “But it couldn’t be him, alone in the middle of this empty field,” thought Rostov. At this time, Alexander turned his head, and Rostov saw his favorite features so vividly etched in his memory. The Emperor was pale, his cheeks were sunken and his eyes sunken; but there was even more charm and meekness in his features. Rostov was happy, convinced that the rumor about the sovereign’s wound was unfair. He was happy that he saw him. He knew that he could, even had to, directly turn to him and convey what he was ordered to convey from Dolgorukov. But just as a young man in love trembles and faints, not daring to say what he dreams of at night, and looks around in fear, looking for help or the possibility of delay and escape, when the desired moment has come and he stands alone with her, so Rostov now, having achieved that , what he wanted more than anything in the world, did not know how to approach the sovereign, and he was presented with thousands of reasons why it was inconvenient, indecent and impossible. "How! I seem to be glad to take advantage of the fact that he is alone and despondent. An unknown face may seem unpleasant and difficult to him at this moment of sadness; Then what can I tell him now, when just looking at him my heart skips a beat and my mouth goes dry?” Not one of those countless speeches that he, addressing the sovereign, composed in his imagination, came to his mind now. Those speeches were mostly held under completely different conditions, they were spoken for the most part at the moment of victories and triumphs and mainly on his deathbed from his wounds, while the sovereign thanked him for his heroic deeds, and he, dying, expressed his love confirmed in fact my. “Then why should I ask the sovereign about his orders to the right flank, when it is already 4 o’clock in the evening and the battle is lost? No, I definitely shouldn’t approach him. Shouldn't disturb his reverie. It’s better to die a thousand times than to receive a bad look from him, a bad opinion,” Rostov decided and with sadness and despair in his heart he drove away, constantly looking back at the sovereign, who was still standing in the same position of indecisiveness. While Rostov was making these considerations and sadly driving away from the sovereign, Captain von Toll accidentally drove into the same place and, seeing the sovereign, drove straight up to him, offered him his services and helped him cross the ditch on foot. The Emperor, wanting to rest and feeling unwell, sat down under an apple tree, and Tol stopped next to him. From afar, Rostov saw with envy and remorse how von Tol spoke for a long time and passionately to the sovereign, and how the sovereign, apparently crying, closed his eyes with his hand and shook hands with Tol. “And I could be in his place?” Rostov thought to himself and, barely holding back tears of regret for the fate of the sovereign, in complete despair he drove on, not knowing where and why he was going now. His despair was the greater because he felt that his own weakness was the cause of his grief. He could... not only could, but he had to drive up to the sovereign. And this was the only opportunity to show the sovereign his devotion. And he didn’t use it... “What have I done?” he thought. And he turned his horse and galloped back to the place where he had seen the emperor; but there was no one behind the ditch anymore. Only carts and carriages were driving. From one furman, Rostov learned that the Kutuzov headquarters was located nearby in the village where the convoys were going. Rostov went after them. The guard Kutuzov walked ahead of him, leading horses in blankets. Behind the bereytor there was a cart, and behind the cart walked an old servant, in a cap, a sheepskin coat and with bowed legs. - Titus, oh Titus! - said the bereitor. - What? - the old man answered absentmindedly. - Titus! Go threshing. - Eh, fool, ugh! – the old man said, spitting angrily. Some time passed in silent movement, and the same joke was repeated again. At five o'clock in the evening the battle was lost at all points. More than a hundred guns were already in the hands of the French. Przhebyshevsky and his corps laid down their weapons. Other columns, having lost about half of the people, retreated in frustrated, mixed crowds. The remnants of the troops of Lanzheron and Dokhturov, mingled, crowded around the ponds on the dams and banks near the village of Augesta. At 6 o'clock only at the Augesta dam the hot cannonade of the French alone could still be heard, who had built numerous batteries on the descent of the Pratsen Heights and were hitting our retreating troops. In the rearguard, Dokhturov and others, gathering battalions, fired back at the French cavalry that was pursuing ours. It was starting to get dark. On the narrow dam of Augest, on which for so many years the old miller sat peacefully in a cap with fishing rods, while his grandson, rolling up his shirt sleeves, was sorting out silver quivering fish in a watering can; on this dam, along which for so many years the Moravians drove peacefully on their twin carts loaded with wheat, in shaggy hats and blue jackets and, dusted with flour, with white carts leaving along the same dam - on this narrow dam now between wagons and cannons, under the horses and between the wheels crowded people disfigured by the fear of death, crushing each other, dying, walking over the dying and killing each other only so that, after walking a few steps, to be sure. also killed. Every ten seconds, pumping up the air, a cannonball splashed or a grenade exploded in the middle of this dense crowd, killing and sprinkling blood on those who stood close. Dolokhov, wounded in the arm, on foot with a dozen soldiers of his company (he was already an officer) and his regimental commander, on horseback, represented the remnants of the entire regiment. Drawn by the crowd, they pressed into the entrance to the dam and, pressed on all sides, stopped because a horse in front fell under a cannon, and the crowd was pulling it out. One cannonball killed someone behind them, the other hit in front and splashed Dolokhov’s blood. The crowd moved desperately, shrank, moved a few steps and stopped again. Walk these hundred steps, and you will probably be saved; stand for another two minutes, and everyone probably thought he was dead. Dolokhov, standing in the middle of the crowd, rushed to the edge of the dam, knocking down two soldiers, and fled onto the slippery ice that covered the pond. “Turn,” he shouted, jumping on the ice that was cracking under him, “turn!” - he shouted at the gun. - It’s holding!... The ice was holding it, but it was bending and cracking, and it was obvious that not only under a gun or a crowd of people, but under him alone, it would now collapse. They looked at him and huddled close to the shore, not daring to step on the ice yet. The regiment commander, standing on horseback at the entrance, raised his hand and opened his mouth, addressing Dolokhov. Suddenly one of the cannonballs whistled so low over the crowd that everyone bent down. Something splashed into the wet water, and the general and his horse fell into a pool of blood. No one looked at the general, no one thought to raise him. - Let's go on the ice! walked on the ice! Let's go! gate! can't you hear! Let's go! - suddenly, after the cannonball hit the general, countless voices were heard, not knowing what or why they were shouting. One of the rear guns, which was entering the dam, turned onto the ice. Crowds of soldiers from the dam began to run to the frozen pond. The ice cracked under one of the leading soldiers and one foot went into the water; he wanted to recover and fell waist-deep. The nearest soldiers hesitated, the gun driver stopped his horse, but shouts were still heard from behind: “Get on the ice, let’s go!” let's go!" And screams of horror were heard in the crowd. The soldiers surrounding the gun waved at the horses and beat them to make them turn and move. The horses set off from the shore. The ice holding the foot soldiers collapsed in a huge piece, and about forty people who were on the ice rushed forward and backward, drowning one another. The cannonballs still whistled evenly and splashed onto the ice, into the water and, most often, into the crowd covering the dam, ponds and shore. On Pratsenskaya Mountain, in the very place where he fell with the flagpole in his hands, Prince Andrei Bolkonsky lay, bleeding, and, without knowing it, moaned a quiet, pitiful and childish groan. By evening he stopped moaning and became completely quiet. He didn't know how long his oblivion lasted. Suddenly he felt alive again and suffering from a burning and tearing pain in his head. “Where is it, this high sky, which I did not know until now and saw today?” was his first thought. “And I didn’t know this suffering either,” he thought. - Yes, I didn’t know anything until now. But where am I? He began to listen and heard the sounds of approaching horses and the sounds of voices speaking French. He opened his eyes. Above him was again the same high sky with floating clouds rising even higher, through which a blue infinity could be seen. He did not turn his head and did not see those who, judging by the sound of hooves and voices, drove up to him and stopped. The horsemen who arrived were Napoleon, accompanied by two adjutants. Bonaparte, driving around the battlefield, gave the last orders to strengthen the batteries firing at the Augesta Dam and examined the dead and wounded remaining on the battlefield. - De beaux hommes! [Beauties!] - said Napoleon, looking at the killed Russian grenadier, who, with his face buried in the ground and the back of his head blackened, was lying on his stomach, throwing one already numb arm far away. – Les munitions des pieces de position sont epuisees, sire! [There are no more battery charges, Your Majesty!] - said at that time the adjutant, who arrived from the batteries that were firing at Augest. “Faites avancer celles de la reserve, [Have it brought from the reserves,” said Napoleon, and, having driven off a few steps, he stopped over Prince Andrei, who was lying on his back with the flagpole thrown next to him (the banner had already been taken by the French, like a trophy) . “Voila une belle mort, [This is a beautiful death,”] said Napoleon, looking at Bolkonsky.