This term has other meanings, see Nesterov.

| City Nesterov Coat of arms |

| A country | Russia, Russia |

| Subject of the federation | Kaliningrad regionKaliningrad region |

| Municipal district | Nesterovsky |

| urban settlement | Nesterovskoe |

| Coordinates | 54°38′00″ n. w. 22°34′00″ E. long / 54.63333° north w. 22.56667° east. d. / 54.63333; 22.56667 (G) [www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=54.63333&mlon=22.56667&zoom=12 (O)] (Z)Coordinates: 54°38′00″ N. w. 22°34′00″ E. long / 54.63333° north w. 22.56667° east. d. / 54.63333; 22.56667 (G) [www.openstreetmap.org/?mlat=54.63333&mlon=22.56667&zoom=12 (O)] (I) |

| Chapter | Kutin Oleg Viktorovich |

| Based | 1539 |

| Former names | until 1938 — Stallupönen until 1946 - |

| City with | 1722 |

| Square | 8 km² |

| Center height | 65 |

| Population | ↘4225[1] people (2016) |

| National composition | Russians - 87.2% Lithuanians - 3.3% Belarusians - 3.2% Ukrainians - 2.7% Germans - 0.8% Poles - 0.5% Gypsies - 0.4% Tatars - 0.3% Chuvash - 0.3% others - 1.3% [2] |

| Timezone | UTC+2 |

| Telephone code | +7 40144 |

| Postcode | 238010 |

| Vehicle code | 39, 91 |

| OKATO code | [classif.spb.ru/classificators/view/okt.php?st=A&kr=1&kod=27224501 27 224 501] |

| Official site | [www.admnesterov.ru/ nesterov.ru] |

Audio, photo and video

on Wikimedia Commons

K: Settlements founded in 1539

Nesterov

(until 1938 -

Stallupönen

(German

Stallupönen

, Polish

Stołupiany

, lit. Stalupėnai), until 1946 -

Ebenrode

(German

Ebenrode

)) is a city in the Kaliningrad region of Russia, the administrative center of the Nesterovsky district and the Nesterovsky urban settlement.

Located near the border with Lithuania, 140 km from Kaliningrad. Railway border crossing with Lithuania.

Story

In ancient times, on the site of Nesterov there was a Prussian settlement with a particularly revered sacrificial stone. There is a report from 1730 about Lithuanians making a pilgrimage to this Prussian altar on Ascension.

With the formation of the Duchy of Prussia, the development of lands covered with virgin forest began in these places. Lithuanians who settled in the Nesterov area took an active part in colonization.

It was founded as a market settlement in Stallupönen in 1539. In 1585, the first wooden church was built there[3]. In 1665, Stallupönen received the right to hold trade fairs, which stimulated its economic growth.[4] In 1719, there was a big fire, as a result of which many buildings burned down, including a wooden church, the local pastor's house and a school. Instead of the one that burned down, a stone church was built in 1726. In 1722, Stallupönen received city rights[3]. During the Seven Years' War from 1757, when it was occupied by Russian troops, and until 1761, it was controlled by the Russian administration.

For border security purposes, a military garrison was stationed in Stallupönen in 1780 (until 1918, there were three light cavalry squadrons in the city)[4].

By 1782, 2,357 people lived in the city[3]. In 1818 the city became the center of the Stallupönen district. In 1860, the Koenigsberg - Eidkunen railway line passed through the city (now the village of Chernyshevskoye). In 1892, the city became a railway junction - the railway connected Stallupönen with Tilsit, and in 1908 the city was connected by a railway line to Poland (Szittkehmen), then passing through Goldap to Gumbinen (now the city of Gusev).

During the First World War, from the autumn of 1914 to February 1915, the city was occupied by Russian troops. In 1938, Stallupönen was renamed Ebenrode.

During the Second World War, a prisoner of war camp Oflag-52 (1D) was located near Ebenrode, where, according to various estimates, from 5 to 8 thousand Soviet soldiers died [3].

In the autumn of 1944, Ebenrode was captured by Soviet troops. Following the Second World War, it became part of the USSR. In 1946, Ebenrode was renamed Nesterov in honor of the Hero of the Soviet Union, Colonel S.K. Nesterov, who died in battles for the city. In the 90s, after the border with Lithuania was formalized, a border and customs control point for railway transport was established. Currently, there are plans to move the border and customs control point to the village of Chernyshevskoye.

- Stallupönen.jpg

Stallupönen. Postcard from the early 20th century.

- Stallupönen (3).jpg

Destruction in the First World War

Nesterov

Nesterov (before 1938 - Stallupönen (German Stallupönen, Polish Stołupiany, lit. Stalupėnai), until 1946 - Ebenrode (German Ebenrode)) is a city in the Kaliningrad region of Russia, the administrative center of the Nesterovsky district and the Nesterovsky urban settlement.

Located near the border with Lithuania, 140 km from Kaliningrad. Railway border crossing with Lithuania.

It is the easternmost city of the Kaliningrad region.

Story

In ancient times, on the site of Nesterov there was a Prussian settlement with a particularly revered sacrificial stone. There is a report from 1730 about Lithuanians making a pilgrimage to this Prussian altar on Ascension.

With the formation of the Duchy of Prussia, the development of lands covered with virgin forest began in these places. Lithuanians who settled in the Nesterov area took an active part in colonization.

It was founded as a market settlement in Stallupönen in 1539. In 1585, the first wooden church was built there. In 1665, Stallupönen received the right to hold trade fairs, which stimulated its economic growth. In 1719, there was a big fire, as a result of which many buildings burned down, including a wooden church, the local pastor's house and a school. Instead of the one that burned down, a stone church was built in 1726. In 1722, Stallupönen received city rights.

During the Seven Years' War from 1757, when it was occupied by Russian troops, and until 1761, it was controlled by the Russian administration.

For border security purposes, a military garrison was stationed in Stallupönen in 1780 (until 1918, there were three light cavalry squadrons in the city).

By 1782, 2,357 people lived in the city. In 1818 the city became the center of the Stallupönen district. In 1860, the Koenigsberg - Eidkunen railway line passed through the city (now the village of Chernyshevskoye). In 1892, the city became a railway junction - the railway connected Stallupönen with Tilsit, and in 1908 the city was connected by a railway line to Russia (Szittkehmen), then passing through Goldap to Gumbinen (now the city of Gusev).

During the First World War, from the autumn of 1914 to February 1915, the city was occupied by Russian troops.

In 1938, as part of a campaign to eliminate place names of Old Prussian (“Lithuanian”) origin, Stallupönen was renamed Ebenrode by the authorities of the Third Reich. During the Second World War, a prisoner of war camp Oflag-52 (1D) was located near Ebenrode, where, according to various estimates, from 5 to 8 thousand Soviet soldiers died.

On October 25, 1944, during an offensive operation, Ebenrode was captured by Soviet troops. Following the Second World War, it became part of the USSR. In 1946, Ebenrode was renamed Nesterov in honor of the Hero of the Soviet Union, Colonel S.K. Nesterov, who died in battles for the city. In the 90s, after the border with Lithuania was formalized, a border and customs control point for railway transport was established. Currently, there are plans to move the border and customs control point to the village of Chernyshevskoye.

Gallery

Population

| Population | ||||||

| 1782 | 1875 | 1890 | 1910 | 1933 | 1939 | 1959[5] |

| 2357 | ↗3763 | ↗4673 | ↗5646 | ↗6294 | ↗6644 | ↘3205 |

| 1970[6] | 1979[7] | 1989[8] | 1996[9] | 1998[9] | 2000[9] | 2001[9] |

| ↗4004 | ↗4745 | ↗4826 | ↗5000 | →5000 | →5000 | →5000 |

| 2002[10] | 2005[9] | 2006[9] | 2007[9] | 2008[9] | 2009[11] | 2010[12] |

| ↗5049 | ↘4900 | →4900 | →4900 | ↘4800 | ↘4703 | ↘4595 |

| 2011[9] | 2012[13] | 2013[14] | 2014[15] | 2015[16] | 2016[1] | |

| ↗4600 | ↘4514 | ↘4436 | ↘4383 | ↘4333 | ↘4225 | |

Architecture, sights

Of the German buildings, the church built in 1927 and the water tower built in 1916 have survived.

- Stallupönen.JPG

Water tower

- Stalupėnai1.JPG

St. Leningradskaya

- Stadtansicht in Stallupönen.jpg

- Stalupėnai.JPG

Road to Nesterov

- Bahnhof Stallupönen.jpg

Train station in Nesterov

- Nesterov Stepan.jpg

Monument to S.K. Nesterov

- Stalupėnai3.JPG

Memorial

- G. Nesterov, church.JPG

Church of the Holy Spirit

- Church of the Holy Spirit (1991). (The Catholic church, built in 1927-1929, was used as a cinema after 1945, and then as a home for pioneers. In 1992 it was given to an Orthodox parish. Consecrated in 1996 in honor of the Descent of the Holy Spirit on the Apostles[17].

- Chapel of the Holy Great Martyr and Healer Panteleimon[17].

- Road sign

The list of cultural heritage sites of local importance includes:

- Administrative building of the early 20th century at 3 Vatutina Street

- Administrative building of the early 20th century at 5 Vatutina Street

- Courthouse of the early 20th century at 10 Oktyabrskaya Street

- Hospital building of the early 20th century on Sovetskaya Street, 12

- Water tower built in 1927 on Chernyakhovsky Street

- Memorial at the mass grave of fallen Soviet soldiers in 1984.

Nesterovsky district is located in the southeast of the Kaliningrad region. It borders with Lithuania in the east and Poland in the south. In the north it borders with Krasnoznamensky, in the west with Gusevsky and Ozersky districts of the region. The district includes one urban and three rural settlements. The administrative center is the city of Nesterov .

The area of the district is 1062 sq. km. The population of the district in 2012 was 16,193 people.

Stallupenen (now the town of Nesterov in documents since 1539. On April 26, 1722, Frederick William I granted the village city rights.

According to data for 1782, 2,357 people lived in the city.

In 1860, the Koenigsberg-Eidkunen railway line (now Chernyshevskoe village) ran through the city.

In 1892, the railway connected Stallupenen with Tilsit (now the city of Sovetsk).

On September 7, 1946, the city of Stallupenen was renamed the city of Nesterov after the Hero of the Soviet Union, Colonel S.K. Nesterov, who died in the battles for the city.

The district was formed as part of the Koenigsberg region on April 7, 1946, renamed Nesterovsky on September 7, 1946 as part of the Kaliningrad region.

Nesterovsky district is one of the most picturesque areas of the region. The true pearl of the region, undoubtedly, is the largest and most beautiful lake in the region - Vishtynetskoe . The unusually large depth (54 m) and significant surface area (16.6 sq. km), as well as the elevation above sea level (+172 m) determine the originality and uniqueness of this basin not only for the Kaliningrad region, but also for the adjacent territories of Poland and Lithuania. This is a kind of “Baikal” of Central Europe, the recreational importance of which will undoubtedly increase.

In the area, and especially near Lake Vishtynets , a large number of objects are concentrated that have an attractive force for tourists and vacationers. These are natural objects, archaeological, historical, cultural. Unlike other rural areas, there are two museums here: the museum of the Trakkenen stud farm in Yasnaya Polyana and the museum of the classic of Lithuanian literature K. Donelaitis in Chistye Prudy, there are ancient arboretums "Yasnaya Polyana" and "Ilyinskoye" , relict lakes, buildings have been preserved in the settlements, whose age is more than 300.

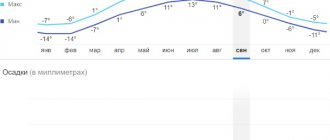

The climate of the region is transitional from marine to temperate continental. The average temperature in January is -2.3 °C, in July + 16.6 °C.

On the territory of the district there is a relict lake Vishtynets - the largest in the region. In 1974, it, together with the Krasnaya (83 km long), was declared a natural monument. In fresh waters there are bream, pike perch, smelt, and eel; in the sea - herring, sprat, smelt, salmon.

The forest zone occupies 26.5% of the district's territory. In these forests there are brown hare, squirrel, marten, fox, roe deer, wild boar, etc. There are many birds. The Rominten Forest (Red Forest) is a natural monument

The Kaliningrad Railway station of the same name is located in Nesterovo This station belongs to the Kaliningrad - Chernyakhovsk - Chernyshevskoye railway line (Lithuanian border).

There are 62 historical and cultural monuments in the area. Among them are several war memorials.

The main attractions of the area include:

— Railway bridge -1900-1901. (Tokarevka village);

- Deer (Imperial) Bridge - Krasnolesye village (The bridge over the Krasnaya River was decorated with bronze figures of deer by the sculptor Richard Friese);

- Mass grave of Soviet soldiers - Krasnolesye village (Mass grave in which 481 Soviet soldiers are buried, who died in October-December 1944 in battles in East Prussia);

— Mass grave of Soviet soldiers (Prigorodnoye village);

— A memorial sign to the soldiers of the Hermann Goering parachute tank corps — in the early 2000s (Yasnaya Polyana village);

— Burial of Russian and German soldiers who died on August 20, 1914 during the Battle of Gumbinen-Goldap - in the second half of the 1910s (Dubovaya Roshcha village, 6 km from the village);

— Museum of the History of Horses - in a restored complex of buildings of the 18th-19th centuries (Yasnaya Polyana settlement, Shkolnaya St., 9);

— Dendrological park on the territory of the park there is a military burial place of the First World War, to which an oak alley leads from the highway - 1732 (in Ilyinsky);

- Chapel of the Holy Equal-to-the-Apostles Grand Duchess Olga - assigned chapel of the Orthodox parish of the Church of the Holy Spirit in Nesterov - 2007 (Lesistoe village, near the road, near the lake);

— a memorial complex associated with the life and work of the classic of Lithuanian literature K. Donelaitis (Chistye Prudy village);

- Catholic church - beginning XX century ( Nesterov )

Official website of the district: www.admnesterov.ru

see also

- [russian-church.ru/viewpage.php?cat=kaliningrad&page=20 Photos of the Church of the Holy Spirit.]

- [russian-church.ru/viewpage.php?cat=kaliningrad&page=21 Photo of the Chapel of the Holy Great Martyr and Healer Panteleimon.]

- [www.panoramio.com/photo/27543619 Water tower]

- [www.panoramio.com/photo/25786506 Road sign]

- [www.panoramio.com/photo/25009676 Nesterov from above]

- [www.panoramio.com/photo/24858079 House of Culture]

- [www.panoramio.com/photo/25785747 Building on Komsomolskaya Street]

- [www.panoramio.com/photo/25786088 Building on Oktyabrskaya Street]

- [www.panoramio.com/photo/28489399 Square in the city center]

Geography

On the territory of the Nesterovsky district there is Lake Vishtynetskoe.

Stallupönen. Postcard from the early 20th century.

Destruction in the First World War

Memorial

Train station in Nesterov

Monument to S.K. Nesterov

Road to Nesterov

Excerpt characterizing Nesterov (Kaliningrad region)

Rostov barely had time to hand over the letter and tell Denisov’s whole business when quick steps with spurs began to sound from the stairs and the general, moving away from him, moved towards the porch. The gentlemen of the sovereign's retinue ran down the stairs and went to the horses. Bereitor Ene, the same one who was in Austerlitz, brought the sovereign's horse, and a light creaking of steps was heard on the stairs, which Rostov now recognized. Forgetting the danger of being recognized, Rostov moved with several curious residents to the porch itself and again, after two years, he saw the same features he adored, the same face, the same look, the same gait, the same combination of greatness and meekness... And the feeling of delight and love for the sovereign was resurrected with the same strength in Rostov’s soul. The Emperor in the Preobrazhensky uniform, in white leggings and high boots, with a star that Rostov did not know (it was legion d'honneur) [star of the Legion of Honor] went out onto the porch, holding his hat under his hand and putting on a glove. He stopped, looking around and illuminating everything around him with his gaze. He said a few words to some of the generals. He also recognized the former chief of the division, Rostov, smiled at him and called him over. The entire retinue retreated, and Rostov saw how this general said something to the sovereign for quite a long time. The Emperor said a few words to him and took a step to approach the horse. Again the crowd of the retinue and the crowd of the street in which Rostov was located moved closer to the sovereign. Stopping by the horse and holding the saddle with his hand, the sovereign turned to the cavalry general and spoke loudly, obviously with the desire for everyone to hear him. “I can’t, general, and that’s why I can’t because the law is stronger than me,” said the sovereign and raised his foot in the stirrup. The general bowed his head respectfully, the sovereign sat down and galloped down the street. Rostov, beside himself with delight, ran after him with the crowd. On the square where the sovereign went, a battalion of Preobrazhensky soldiers stood face to face on the right, and a battalion of the French Guard in bearskin hats on the left. While the sovereign was approaching one flank of the battalions, which were on guard duty, another crowd of horsemen jumped up to the opposite flank and ahead of them Rostov recognized Napoleon. It couldn't be anyone else. He rode at a gallop in a small hat, with a St. Andrew's ribbon over his shoulder, in a blue uniform open over a white camisole, on an unusually thoroughbred Arabian gray horse, on a crimson, gold embroidered saddle cloth. Having approached Alexander, he raised his hat and with this movement, Rostov’s cavalry eye could not help but notice that Napoleon was sitting poorly and not firmly on his horse. The battalions shouted: Hurray and Vive l'Empereur! [Long live the Emperor!] Napoleon said something to Alexander. Both emperors dismounted from their horses and took each other's hands. There was an unpleasantly false smile on Napoleon's face. Alexander said something to him with a gentle expression. Rostov, without taking his eyes off, despite the trampling of the horses of the French gendarmes besieging the crowd, followed every move of Emperor Alexander and Bonaparte. He was struck as a surprise by the fact that Alexander behaved as an equal with Bonaparte, and that Bonaparte was completely free, as if this closeness with the sovereign was natural and familiar to him, as an equal, he treated the Russian Tsar. Alexander and Napoleon with a long tail of their retinue approached the right flank of the Preobrazhensky battalion, directly towards the crowd that stood there. The crowd suddenly found itself so close to the emperors that Rostov, who was standing in the front rows, became afraid that they would recognize him. “Sire, je vous demande la permission de donner la legion d'honneur au plus brave de vos soldats, [Sire, I ask your permission to give the Order of the Legion of Honor to the bravest of your soldiers,” said a sharp, precise voice, finishing each letter . This was said by the short Bonaparte, looking directly into Alexander’s eyes from below. Alexander listened carefully to what was said to him, and bowing his head, smiled pleasantly. “A celui qui s'est le plus vaillament conduit dans cette derieniere guerre, [To the one who showed himself bravest during the war," added Napoleon, emphasizing each syllable, with a calm and confidence outrageous for Rostov, looking around the ranks of Russians stretched out in front of there are soldiers, keeping everything on guard and motionlessly looking into the face of their emperor. – Votre majeste me permettra t elle de demander l'avis du colonel? [Your Majesty will allow me to ask the colonel’s opinion?] - said Alexander and took several hasty steps towards Prince Kozlovsky, the battalion commander. Meanwhile, Bonaparte began to remove the glove from his white, small hand and, tearing it, threw it away. The adjutant, hastily rushing forward from behind, picked her up. - Who should I give it to? – Emperor Alexander asked Kozlovsky not loudly, in Russian. - Whom do you order, Your Majesty? “The Emperor frowned with displeasure and, looking around, said: “But you have to answer him.” Kozlovsky looked back at the ranks with a decisive look and in this glance captured Rostov as well. “Isn’t it me?” thought Rostov. - Lazarev! – the colonel commanded with a frown; and the first-ranked soldier, Lazarev, smartly stepped forward. -Where are you going? Stop here! - voices whispered to Lazarev, who did not know where to go. Lazarev stopped, looked sideways at the colonel in fear, and his face trembled, as happens with soldiers called to the front. Napoleon slightly turned his head back and pulled back his small chubby hand, as if wanting to take something. The faces of his retinue, having guessed at that very second what was going on, began to fuss, whisper, passing something on to one another, and the page, the same one whom Rostov saw yesterday at Boris’s, ran forward and respectfully bent over the outstretched hand and did not make her wait either one second, he put an order on a red ribbon into it. Napoleon, without looking, clenched two fingers. The Order found itself between them. Napoleon approached Lazarev, who, rolling his eyes, stubbornly continued to look only at his sovereign, and looked back at Emperor Alexander, thereby showing that what he was doing now, he was doing for his ally. A small white hand with an order touched the button of soldier Lazarev. It was as if Napoleon knew that in order for this soldier to be happy, rewarded and distinguished from everyone else in the world forever, it was only necessary for him, Napoleon’s hand, to be worthy of touching the soldier’s chest. Napoleon just put the cross to Lazarev's chest and, letting go of his hand, turned to Alexander, as if he knew that the cross should stick to Lazarev's chest. The cross really stuck. Helpful Russian and French hands instantly picked up the cross and attached it to the uniform. Lazarev looked gloomily at the little man with white hands, who was doing something above him, and, continuing to keep him motionless on guard, again began to look straight into Alexander’s eyes, as if he was asking Alexander: whether he should still stand, or whether they would order him should I go for a walk now, or maybe do something else? But he was not ordered to do anything, and he remained in this motionless state for quite a long time. The sovereigns mounted and rode away. The Preobrazhentsy, breaking up the ranks, mixed with the French guards and sat down at the tables prepared for them. Lazarev sat in a place of honor; Russian and French officers hugged him, congratulated him and shook his hands. Crowds of officers and people came up just to look at Lazarev. The roar of Russian French conversation and laughter stood in the square around the tables. Two officers with flushed faces, cheerful and happy, walked past Rostov. - What is the treat, brother? “Everything is on silver,” said one. – Have you seen Lazarev? - Saw. “Tomorrow, they say, the Preobrazhensky people will treat them.” - No, Lazarev is so lucky! 10 francs life pension. - That's the hat, guys! - shouted the Transfiguration man, putting on the shaggy Frenchman’s hat. - It’s a miracle, how good, lovely! -Have you heard the review? - the guards officer said to the other. The third day was Napoleon, France, bravoure; [Napoleon, France, courage;] yesterday Alexandre, Russie, grandeur; [Alexander, Russia, greatness;] one day our sovereign gives feedback, and the next day Napoleon. Tomorrow the Emperor will send George to the bravest of the French guards. It's impossible! I must answer in kind. Boris and his friend Zhilinsky also came to watch the Transfiguration banquet. Returning back, Boris noticed Rostov, who was standing at the corner of the house. - Rostov! Hello; “We never saw each other,” he told him, and could not resist asking him what had happened to him: Rostov’s face was so strangely gloomy and upset. “Nothing, nothing,” answered Rostov. -Will you come in? - Yes, I’ll come in. Rostov stood at the corner for a long time, looking at the feasters from afar. A painful work was going on in his mind, which he could not complete. Terrible doubts arose in my soul. Then he remembered Denisov with his changed expression, with his humility, and the whole hospital with these torn off arms and legs, with this dirt and disease. It seemed to him so vividly that he could now smell this hospital smell of a dead body that he looked around to understand where this smell could come from. Then he remembered this smug Bonaparte with his white hand, who was now the emperor, whom Emperor Alexander loves and respects. What are the torn off arms, legs, and killed people for? Then he remembered the awarded Lazarev and Denisov, punished and unforgiven. He caught himself having such strange thoughts that he was frightened by them.

City of Nesterov. Names of Lipetsk residents on the map of Russia

09:00, 05 May 2017

Special projects

On the map of the Russian Federation there is a small town of Nesterov with a population of just over four thousand people. It is the administrative center of the Nesterovsky district and the Nesterovsky urban settlement of the Kaliningrad region. It was named in honor of our fellow countryman, a native of the village of Talitsky Chamlyk, Dobrinsky district, Stepan Nesterov, who died in the battles for this city on October 20, 1944.

Until 1938 the city was called Stallupönen, from 1938–1946 it was called Ebenrode. Following the Second World War, it became part of the USSR. In 1946, Ebenrode was renamed Nesterov.

During World War II, the Oflag-52 (1D) prisoner-of-war camp was located near Ebenrode, where, according to various estimates, between five and eight thousand Soviet soldiers died.

In the autumn of 1944, Ebenrode was taken by Soviet troops. In the 90s, after the border with Lithuania was formalized, a border and customs control point for railway transport was established in the city.

Located 140 kilometers east of the regional center, near the border with the Republic of Lithuania.

Nesterov is a railway station on the Kaliningrad-Vilnius-Moscow line. The nearest cities are Gusev (25 km by road) and Krasnoznamensk (37 km). The highway connecting Kaliningrad with Moscow passes through the city. On the territory of the district there is the largest 24-hour international automobile crossing “Chernyshevskoe” (Russia-Lithuania). Nesterovsky district also has a border with Poland. The economy of the municipality is dominated by the agricultural sector.

Nesterov Stepan Kuzmich - deputy commander of the 2nd Guards Red Banner Tatsin Tank Corps for the combat unit of the 3rd Belorussian Front, guard colonel.

During the Soviet-Finnish War of 1939-1940, Stepan Kuzmich was the chief of staff of a tank battalion. In 1941 he graduated in absentia from the Military Academy of Armored Forces.

From October 1941, Nesterov was at the front and at the beginning of the Battle of Stalingrad he commanded a tank brigade.

After the defeat of the Germans on the Volga, Nesterov's tank brigade received the title of Guards. On the Kursk Bulge in the famous battle of Prokhorovka, Lieutenant Colonel Nesterov personally led the tankers into the attack, being in the thick of the battle. In August 1943, the brigade was transferred to the Western Front. Tanks of brigade commander Nesterov liberate Smolensk and Yelnya. For excellent execution of the command’s order to defeat the enemy in Yelnya, the brigade receives the honorary name “Yelninskaya”.

In April 1944, Nesterov's brigade was the first to break into the southeastern outskirts of Minsk in the early morning of July 3, 1944. For the liberation of the capital of Belarus, the 26th Guards Tank Brigade was awarded the Order of the Red Banner. Subsequently, the Nesterovites contributed to the encirclement of a large enemy group and participated in its liquidation.

After the liberation of Belarus, soldiers of the 26th Guards Brigade crush the enemy in Lithuania. Nesterov's tankers especially distinguished themselves during the liberation of Vilnius and crossing the Neman, for which the brigade was awarded the Order of Suvorov, 2nd degree.

When the tankers came close to the border with East Prussia, Guard Colonel Nesterov parted with his brigade, with which he walked along front-line roads from the Don to Lithuania. He, as one of the experienced and talented commanders, is appointed to the post of deputy commander of the 2nd Guards Tatsin Tank Corps. In October 1944, Stepan Kuzmich led the crossing of the Pissa River in the area of the settlement of Kassuben, located 14 kilometers south of the city of Stallupenen (now the city of Nesterov, Kaliningrad region) and ensured further successful actions of the corps. At the head of one of the tank brigades, he personally pursued the enemy.

Developing the offensive, the tankers, supported by a motorized rifle brigade, reached the city of Stallupenen. At the height of the battle on October 20, 1944, Guard Colonel Stepan Kuzmich Nesterov was killed by a German bullet west of the town of Kassuben (now the village of Ilinskoye, Nesterovsky district, Kaliningrad region). However, the operation, launched under the skillful leadership of our fellow countryman, was completed with honor: the city of Stallupenen was taken and the fascist division “Hermann Goering” was defeated. The bridgehead for the Red Army's general offensive against East Prussia was conquered.

Guard Colonel Stepan Nesterov was initially buried with military honors in a park in the city of Kaunas (Lithuania). Later he was reburied in a mass grave in the city of Nesterov, Kaliningrad region.

By decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of April 19, 1945, for the courage and heroism shown in the fight against the Nazi invaders, Guard Colonel Stepan Kuzmich Nesterov was posthumously awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

In 1946, the city of Ebenrode was renamed Nesterov.

In 1956, a monument to the Hero of the Soviet Union Nesterov was erected in the center of the city of Nesterov. In 2005, the old monument was replaced with a new one made of bronze.

A bust of Nesterov was installed in the village of Dobrinka, Lipetsk region. A secondary school in the village of Talitsky Chamlyk, Dobrin district, is named after Nesterov. There is a memorial plaque on her building.

Also, memorial plaques were installed at one of the stations of the Kaliningrad Railway and in Lipetsk on Hero Street. Nesterova Street in Lipetsk was formed on May 21, 1957. It connected Gagarin and Telman streets of the regional center in the area of Lipetsk secondary school No. 24.

In addition to the city of Nesterov, in the Kaliningrad region the cities of Guryevsk and Gusev are named after natives of the Lipetsk land.

Matvey SUSHKOV

Photos from the websites of “Heroes of Russia” and the administration of the Nesterovsky district, from the Great Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Kaliningrad Region and the LipetskMedia archive.

Subscribe to our channel in Yandex.Zen

Facebook Twitter